Coleen age 15 on Burwell Bldg porch Coleen age 15 on Burwell Bldg porch The sixth of seven children from a Nash County family wracked by death, illness and other “sad circumstances,” Colleen Bunting came to Methodist Orphanage at age 7. Her younger brother, Stanley, arrived two months later. Moving to the Raleigh campus: I remember that day like it was yesterday. It was March 17, on a Friday. I was living, temporarily as it turned out, with an aunt (one of my mother’s sisters). I knew in advance that I was going to move to the orphanage in Raleigh.

1 Comment

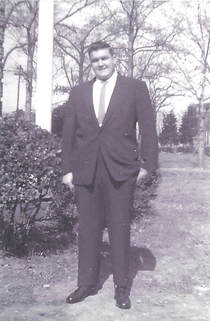

Bill & Peggy Griffin Bill & Peggy Griffin My place in Methodist Home for Children’s history—actually begins in 1917 with an 8-year-old named Ray Griffin from Beaufort County. This boy was my father. His mother died giving birth to his sister, and his father was left alone with no wife by his side to raise six children. So the Methodist church in Washington, N.C., reached out to the orphanage to see if it could take some of these children, and my father, his three sisters and one brother were admitted in 1917. They lived at the campus with many other orphanage brothers and sisters until they graduated from high school. They were helped at a time when there were no other means for them and for their father to support them. They all went on to live productive lives.  Wade Smith in 1957, the year he graduated from Methodist Orphanage. Wade Smith in 1957, the year he graduated from Methodist Orphanage. Wade Smith was born near Enfield in Halifax County to “a poor, very poor” sharecropping family. He was the only one of six children in his family to complete high school, much less college, he says, because of Methodist Orphanage. Wade was 10 years old in 1950 when his parents ended their 27-year marriage, and his mother and a county welfare worker arranged for him to go to Methodist Orphanage with his two younger sisters, Jean, 8, and Becky, 6. He lived seven years on the MO campus and learned the benefits of kindness, opportunity and hard work. “The orphanage taught you that nothing was free,” he says. “You had to work hard to get anything.” Joe Pearce swears that when he lived at Methodist Orphanage/Methodist Home for Children, he raked a million leaves. “And I mean a million,” he repeats firmly.

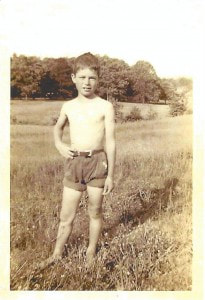

His family lived in rural Wake County near Zebulon, and Joe came to the orphanage in 1957 with two younger brothers. His yard chores spanned almost all of his eight years at MO/MHC, though Joe discovered the secret to the system before he left in 1965. “After classes at Broughton High School, I would race back to campus and be the first one to find the grounds superintendent, Mr. McCloud. Being first in line meant I got to pick the best job—so no more raking leaves!”  Kramer Jackson at age 8 Kramer Jackson at age 8 The circumstances of my journey to the Methodist Orphanage in Raleigh are not unlike those of many children who grew up there. My father died a sudden and tragic death in May 1941, leaving behind a 23-year-old widow with three children. At 2½, I was the middle child with a 6-year-old sister, Ruth, and a 2-week-old brother, James. Our mother was devastated by our father’s death. With a 4th-grade education, no income and no experience other than the work required of a child growing up on a tenant farm, she was unable to face the bleakness of her circumstances.  Living away from home and apart from their mothers, two 8-year-old girls bonded in a big way when they met at Methodist Home for Children 48 years ago. Mona and Terri did everything together. They were best friends—strength and sanctuary for each other under some difficult circumstances. The girls lost touch after they left MHC, and each went on to build her own life. They hadn’t spoken in decades when Mona recognized her friend in Facebook photos posted at an MHC alumni event. “I was clicking through the picnic photos pretty fast, and I was half standing to walk away from my computer when her image made me do a double-take and sit back down,” Mona says. The two exchanged contact information through the alumni association. That night, Terri called Mona, and they talked until 3 a.m., catching up. “It was as if we had not been apart a single day,” Terri says. |

Archives

July 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed